Women at the Heart of the Men of the Trees

International Women’s Day 2017 asks the question of its participants, ‘will you be bold for change?’; an impassioned call for strong and decisive action in the face of a world where women’s rights are far from being a given. As a researcher looking at the history of the International Tree Foundation (the Men of the Trees as it was previously known) through the work of its founder, Richard St. Barbe Baker, it might seem that women were rather thin on the ground. But that couldn’t be further from the truth, and a glance back through some early issues of the journal Trees proves to be a very straightforward way to refute the assumption that there were few women in the organisation, with one in particular who I’d like to draw your attention to today.

Women at the heart of the Men of the Trees

From the organisation’s earliest days, Richard St. Barbe Baker found friendship and guidance from some key female collaborators and colleagues, most notably Claudia Stuart Coles and Ursula Grant Duff. Claudia Coles was the person who introduced the Bahá’í faith to him in 1924, and the intensity of their connection meant that it was to Coles that Baker sent a letter outlining his ambitions to join the fight to save the Redwoods of California when he thought he was close to losing his life after an accident on board a ship in 1930.

Ursula Grant Duff was an early member of the organisation, and someone who links the Men of the Trees to the Eugenics Society, of which Marie Stopes and John Maynard Keynes were members, and which forms an unattractive but critical part of the group’s history, as described in Angus McLaren’s book Reproduction by Design: Sex, Trees and Test-tube Babies in Interwar Britain. The presence of eugenics in the history of the Men of the Trees is not something to be shied away from. On a day which champions change for women around the world, it allows us to look back at the intellectual, environmental and political legacies of other influential female supporters of the organisation, a list which includes the Quaker and philanthropist Elizabeth Cadbury, the suffragist Maude Royden and Lady Evelyn Balfour, founder of the Soil Association.

It was serendipitous that over the course of the research that I am otherwise undertaking for my PhD on Richard St. Barbe Baker, I happened to pick up the Summer / Autumn 1965 issue of Trees and Life. Each edition is a treasure trove of insight into the workings and outlook of the organisation and often there is a real intimacy to reading a copy, as one is transported back to the issues of the time. The front cover has a reproduction of one of Baker’s images from Dance of the Trees, entitled ‘In New Zealand as everywhere, the Forest is Mother of the Rivers’ and the inside pages announce it as ‘A Magazine for Tree Lovers and Socially Conscious Foresters’. Within the journal is an article by a woman called Wendy Campbell-Purdie, entitled ‘Fighting the Desert’, along with (in the case of the copy I have on my desk) a cutting from The Guardian from Wednesday September 29th 1965, with the headline ‘Woman against the desert’ by the socialist and pacifist Fenner Brockway.

An article that appeared in The Guardian in 1965

Wendy Campbell-Purdie, a women set on reforesting the desert

Wendy Campbell Purdie is a significant part of the story of the Men of the Trees. When Baker’s obituary was published in The Times in 1982 it was her project in Algeria which was alluded to as being the nearest to realising his greatest ambition for a Green Front against the desert. Campbell-Purdie’s account of the meeting that led her to establish her own programme of afforestation in Morocco and then Bou Saada in Algeria paints a portrait of Richard St. Barbe Baker which reveals him to be as extraordinarily compelling as he comes across in other accounts, but with a great deal more human frailty. She had travelled from Corsica to England to discuss the introduction of Corsican pine seed but they never reached that subject. Instead, Campbell-Purdie recalls barely having arrived before her host announced his ambition to reclaim the Sahara:

“He would speak of nothing else, talking steadily through breakfast and lunch and tea and supper and in the long intervals. My brain was stretched, trying to follow his monologue on subterranean waters, the thornscrub that marks the underground watercourses, the miserable state of the Touareg and Bedouin who are losing their grazing lands. And so much more. He convinced me. In the night I could sleep and dream and daydream. The words of Isiah came back to me: “The desert shall rejoice and blossom as the rose.”

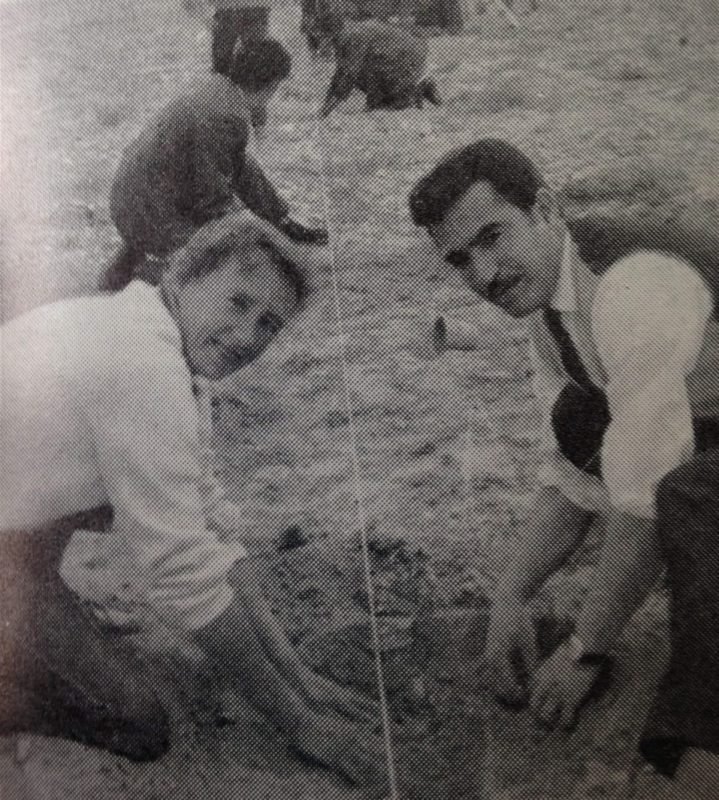

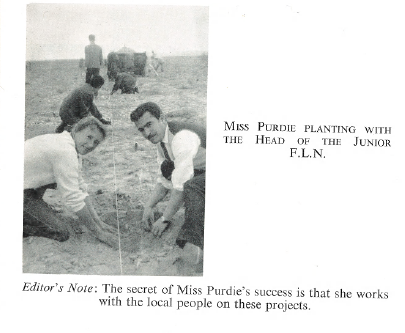

Photo from the 1965 edition of Trees

This encounter was around 1959 and Campbell-Purdie, deciding to dedicate herself to the cause, later went to one of the World Forestry Charter Luncheons at the Dorchester where Baker had intended to introduce her to a representative from Morocco. The resulting contact was never made and the events of the day, as recounted by Campbell-Purdie, show a much more vulnerable man: too ill to receive the guests. Campbell-Purdie and another associate acted for him and, after his speech, Baker collapsed and was taken to Westminster Hospital. The advice and guidance never materialised and Campbell-Purdie was left to ‘try elsewhere to find a gateway to the Sahara’.

This image, of a woman heading out alone to reforest the desert, is one that challenges the vision of humanity coming together, as in the wider vision, to work to combat desertification. Instead, it is one individual with a sense of commitment to an idea bigger than herself, setting out to begin a task that it might otherwise take the cooperation of whole nations to achieve. In her Trees article she describes the success she had in North Africa:

“Trees I planted in Tiznit, Morocco, in January and December 1960 are now twice as tall as a man. One of the thousand trees I planted near Bou Saada in March 1964 is now taller than the large Conservator of Forests in Algeria. He was startled.”

My research into Campbell-Purdie reaches a dead end as there is no accessible evidence to say what happened to her and her activities in Morocco and Algeria. Yet, just to revisit her contribution ensures the recognition of her role in actively seeking change, and this is something she shares with other important women in the environmental movement; women like Wangari Maathai whose significance in Kenya and around the world as an advocate for both the environment and for women as interrelated and interdependent issues, is as pressing now as when she championed the Green Belt Movement.

Camilla Allen visiting Women’s tree nurseries in Kenya. Credit: Max Charles 2017

As a female researcher I get great satisfaction from knowing that there are also links between Richard St. Barbe Baker and Maathai, but that her powerful advocacy for trees came from her own passion and insight, not something that needs to be attributed to Baker. The International Tree Foundation empowers women to be bold for change. I witnessed first-hand some of the agroforestry and reforestation projects that are being supported in Kenya where women are integral to the care and planting of trees. That is something to celebrate and build upon on International Women’s Day!

(For anyone who is interested in reading more about Cambell-Purdie she also wrote a book about her work with Fenner Brockway and which has a foreword by Iris Murdoch called Woman Against the Desert, published by Victor Gollancz in1967.)

About the author: Camilla Allen is conducting research into the work of Richard St Barbe Baker. You can read more from Camilla at www.radicalsylviculture.comDonate Today

Support communities on the front lines of the climate crisis to plant trees, restore ecosystems and improve their livelihoods.